Here’s A List

William Burroughs, Kather Acker, Frantz Fanon, Edward Albee, DH Lawrence, Che Guevara, Antonin Artaud, Amiri Baraka, Simone De Beauvoir, Samuel Beckett, Jorge Luis Borges, Bertolt Brecht, Charles Bukoski, Albert Camus, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Jean Genet, Alan Ginsburg, Gunter Grass, Vaclav Havel, Henry Miller, Chester Himes, Eugene Ionesco, Jack Kerouac, Timothy Leary, Yukio Mishima, Josephine Miles, Vladimir Nabokov, Pablo Neruda, Frank O’Hara, Harold Pinter, Raymond Queneau, Jean-Paul Sartre, Susan Sontag, Terry Southern, Gary Snyder, Tom Stoppard, John Kennedy O’Toole, and Malcolm X.

There's something unusual about that list, and it’s not the fact it includes 5 Nobel prize winners--it’s that they all had the same publisher: Grove Press. And almost always because no-one else in America would publish them.

It wasn’t a big press and it was largely funded by pornography: an imprint called The Victorian Library which published books like Blind Lust, A Nymph In Paris, Ravished on the Railway, and a line of novels about spanking.

If you’re wondering when it became legal to put out an RPG book called Fish Fuckers or Fuck for Satan in the US, you’ll find out about the Lady Chatterly’s Lover case of 1959—and Grove Press’ head: Barney Rosset.

Barney then eagerly again went to the mat for Naked Lunch in 1962 and then fought another court case for the right to publish Tropic of Cancer in 1964.

That was the first year Grove was turning a profit—Rosset took over Grove in 1951.

He never had to go to trial for the pornography.

____

QUIZ (no fair googling)

Which of Grove’s books received the following response:

“Borrowed this from a friend after hearing the high praise, and the whole thing just seems to be a childish exercise in cramming as many instances of “fuck” into the text as possible.”

A) Lady Chatterly’s Lover in 1959

B) Naked Lunch in in 1962

C) Tropic of Cancer in 1964

Keep reading for the answer.

The Word "Censorship" Usually Means You're Lying

When discussing art in 2018, the phrases “freedom of speech”, “censorship” and “once upon a time” all have something in common—usually they all tell you the person talking is about to say something full of shit. Pro- or con-.*

When it comes to “freedom of speech” or “censorship”, the “pro” person is usually about to make an argument falsely equating a private person not wanting to deal with or promote some speech with a government making a law against it.

The “con” person is usually about to make an argument falsely equating a creator or fan’s claim that a criticism is unfair, invalid or irresponsible with that creator or fan trying to claim that the criticism is-, or will lead to-, a law against it.

They’re both ignoring an issue nobody wants to talk about:

Someone is upset about a work of art and they either should or shouldn’t be.

Discussing “censorship” is discussing the consequences of that upsetness, not the validity. We all agree on the consequences: “I don’t advocate Censorship. What I am saying is…”.

This is a middle-class confrontation-avoidance strategy. It sounds a lot less judgmental to go “This book has two gentlemen adopting a baby in it and if that offends you you’re free to not buy it” than to go “This book has two gentlemen adopting a baby in it and if that offends you, you are terrible and should change.”

The second thing is the true one, but it makes the fight more intense, so people have instead made an agreement: creators get to make whatever they want including pointlessly bigoted things, critics get to make any accusations they want about anything including paranoid, unsupported ones.

That’s important because this compromise—the agreement to disagree about the speech or the art while agreeing it shouldn’t be Censored—means that we can endlessly postpone a more meaningful debate about what exactly the good things about art are supposed to be that supposedly make all this arguing worthwhile.

Without that discussion of the value of created things we get to pretend we agree with each other longer—which helps us build cars and snout-to-tail pig-cooking restaurants and massively multiplayer online RPGs together.

It also helps everyone do their favorite thing which is to ignore capitalism: ignore how art and criticism function in the market. It ignores how successful art can encourage copies of itself until its ideas become unavoidable even if you did just "not buy it" and how public criticism literally has no purpose unless it influences companies and consumers to choose more of the art it likes and less of the art it doesn’t and so effectively throttle the undesirable art.

You don't publicly complain about a book without also hoping someone will do something in response. And the publicness makes that response possible.

There is, in effect, a cultural Cold War, where neither side defines its borders because the only thing they're both sure of is neither side wants the nuclear option. Lying, shifting borders and alliances, making locally convenient arguments--all the standard covert ops: sure. Standing up and going "Ok ends here, at this line, and you are standing on the other side of it" would be to invite people to vote or make laws and pass amendments and nobody's sure they want to go that far.

Back to Grove Press:

There is no major publisher that wouldn't recognize not just the value, but the primacy of the authors Grove published--yet there was no major publisher that would've taken the risks necessary to publish them.

In addition to literally millions of (1960’s) dollars of legal fees, 13 years is a long time to publish weird books without making any money. Effectively speaking, Barney Rosset had to buy America the right to freedom of speech. And, if you look at that list of authors and realize how very little 20th century literature would be left without them and remember nobody else at that time would have them, he basically bought the country’s right to have any halfway decent books at all.

Good Stuff Results In Moral Panics

It’s hard to think of any mass introduction of anything both good and new to the English-speaking world that isn’t accompanied by a moral panic: Ulysses went on trial for obscenity, metal, punk, hip-hop and even Prince and Madonna were targeted by moral guardians, the National Endowment for the Arts—that is: US government funding for art as a concept— basically no longer exists because of the culture wars of the 1990s, Donald Trump’s trying to blame video games for violence, Fredric Wertham gutted comics (especially horror) by using fraudulent evidence to bring in the comics code, and, of course that whole thing with D&D’s satanic panic. Get ready for one about anime when the Republicans find out what it is.

Because it’s so easy to look back and laugh (saying Twisted Sister’s We’re Not Gonna Take It promoted violence and Cyndi Lauper She Bop was sexfilth seems pretty quaint by today’s standards) it’s easy to overlook the very real damage that rhetorical and economic warfare against creators can and does do to real lives.

The PMRC’s “Parental Advisory” sticker on albums seems like a joke but it decided for a very long time who did and didn’t get into massive chains like Wal-Mart. While Madonna and Prince and Twisted Sister made it out of the PMRC-era ok, countless lesser-known and up-and-coming musicians had their careers completely derailed by the economics of the situation. We tend to think the fine artists associated with Congressional freak-outs walk away more famous—all press is good press, right?—but, for example, Ron Athey, an artist famous to me in art school for being accused of “spraying AIDS-infected blood on the audience” (he didn’t) basically couldn’t perform in the US for much of his career and has had a day job ever since.

As for Rosset and Grove Press: in ’68, someone threw a grenade through his window.

|

| ....and, of course, the FBI had a massive file on him |

There Is A Price To Everything

No-one will ever throw a grenade through James Edward Raggi IV’s window—and there won’t be delicious anecdotes in The Atlantic by adoring literati when he dies. And nothing he published will upset the American public on a grand scale.

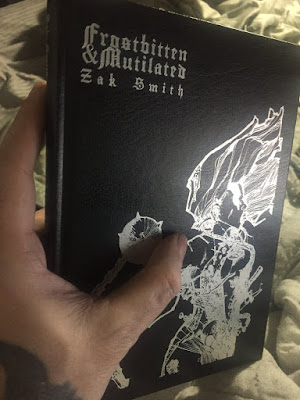

But there's nobody else really doing what Lamentations of the Flame Princess does: the mainstream publishers repeatedly and explicitly say they’re making what they think the market wants, most indies aren't paying people enough to attract real talent while simultaneously presenting them halfway decently, the other OSR publishers are putting out some good stuff but not with the same full-court press of writing, illustration, binding and experimental content. A few cool publishers following in his footsteps are just getting started—but they’re not full-time yet. Many major RPG freelancers go to James because their mainstream publishers either won't let them do what they want or they know they won't do it the way it needs to be done.

And James has—very voluntarily—taken up the role of being That Guy Who Publishes The Good, Scary Stuff in the 2018 RPG environment and that entails real risk and is a real pain in the ass for one man alone in Finland with a house full of boxes. He has chosen trouble.

Peter Mayer, who ran Avon and Penguin: "Barney chose these battles, there was nothing inadvertent in what came down,"--just like James chose all his (his first 2 books besides his own were Carcosa and the one by the porn guy). They both picked stupid fights on purpose at great personal cost in the name of creepy quality to far less acclaim than they deserve while the rest of us just read Jean-Paul Sartre and Qelong and count our money.

LotFP is successful—but in projecting and promoting that success (partially to move units, but also to encourage other similar ventures)—we somewhat elide the shittiness that comes with it: retailers and other potential partners get skittish and sometimes just say no, in ways and for reasons James doesn’t much talk about. The legendary online dramafests against LotFP are the tip of a really gross behind-the-scenes iceberg you don't want to know the half of.

And why? Complaints. Internet complaints.

But, unlike Barney Gosset, James was not born rich. James was broke until Red & Pleasant Land in 2015--that is, until after the orgy of harassment from the supposedly-woke when I consulted on 5th edition D&D and after RPL won all those Ennies. The death threats, the rape threats, the smears, all that--James was full-time putting out the LotFP Grindhouse Edition and Vornheim and Carcosa and paying all that money to all those illustrators all through all of that for no better and often less than shitty-day-job reward for half a decade.

LotFP has been satirized as a grossout factory, but just like Barney and all this porn he published, James has never really been raked over the coals for Vaginas Are Magic or Fuck for Satan--nor have his many lowbrow competitors. What makes people mad isn't the vulgarity, it's the praise.

Remember the quiz?

“Borrowed this from a friend after hearing the high praise, and the whole thing just seems to be a childish exercise in cramming as many instances of “fuck” into the text as possible.”

Ok, trick question: this isn’t someone from 1962. Someone said that in the last year about Veins of the Earth.

And this wasn’t some nun or white nationalist who’d stumbled across a copy by accident in a hospital waiting-room, this is a supposedly woke gamer who thinks everyone should use the X-Card.

Why borrow all this trouble?

The simplest way to put it is: he enjoys and believes in things that lots of other people also believe in called horror, and metal, and gore.

Because James believed that Carcosa was a plunge into an unexplained world of alien deep time.

Because he believed that Qelong was the kind of pessimistic historical hellscape nobody else would do justice to.

Because whatever value stomach-bursting, dead baby, body-horror offers to the people who go to horror movies and horror conventions and horror music is as applicable in his medium as in anyone else’s.

What value is that?

Sarah Horrocks says it better than anyone else could.

But, also, without going in to too many details: James has been through some gruesome things. People very close to him have been through gruesomer things. When he sees a bloodless throat-cutting in a mainstream movie this strikes him as false and wrong and not how he wants to do it.

The moral of this story and the moral of LotFP stories is: there is a price to things.

Why else?

Because, beyond horror, James believes in what his authors are doing as fun and good and original and better than everything else out there.

And it is not a coincidence that these are the most controversial ones. People don’t get to be good at their job by simply reimagining what others already have—and about half of what others already haven’t imagined yet is things where the first few steps are wrong, and the good stuff is past them, way down in the basement.

And he does this while hiring women, while hiring transfolk, while paying everyone well and on-time while being transparent and letting them see the math--while rival indie publishers are seemingly in a contest to how often they can embarrass themselves while keeping a fresh-faced clean-shaven woke image. I mean, it's a cliche but sometimes the good guy isn't the one waving his white hat around.

There's no other RPG publisher who has taken on as much risk on behalf of other people as LotFP.

Next time another publisher starts talking about diversity, innovation or fairness in games, ask them: How much have they risked in the name of these things?

When Barney Rosset reached out to a founder at Random House during the first court case, he replied:

I can’t think of any good reason for bringing out an unexpurgated version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover at this late date. In my opinion the book was always a very silly story, far below Lawrence’s usual standard, and seemingly deliberately pornographic . . . . I can’t help feeling that anybody fighting to do a Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1954 is placing more than a little of his bet on getting some sensational publicity from the sale of a dirty book.

Fifteen years later, Jacob Epstein from Random House had this to say about Barney:

When the history of publishing is written, Barney will have a place in it. He's bright. He takes a lot of risks that look frivolous to many people, but there's a serious radical impulse behind them all. He's altered the climate of publishing to everybody's advantage.

That’s James right there. Only he’s doing it in a world nobody will ever care about that half consists of people who treat him like he's selling meth.

I think in the end though, listening to him talk, he doesn’t just like the stuff: he has an idea about role-playing games. They give you stats and tell you what you could buy and tell you where you should go and, if you’re smart, you don’t do it. You go somewhere else, you avoid the trap, you ransom the patron, you avoid the railroad: this is what James learned. This is another lesson of these games.

This is why he writes dungeons where doing the suggested thing always kills you. He’s offended by the vision of human beings as animals which do something just because it’s suggested: by an image or a word or an association or a tradition. He’s offended by the idea that we accept this impulse and cater to it. Let's leave an idea unaddressed because it might brush up against a suggestion.

James doesn’t want to train people to fuck fish or murder babies—he wants a world full of people who can read that kind of gibberish and all the gibberish that the world asks us to read everyday on Facebook that doesn’t even have the decency to label itself as “fiction” and walk away still being human, still being capable of weighing things with the salt they deserve, still being able to think for themselves.

If pumping out the number of books he does a year, while rolling from con to con like a drunk circus bear on the advances and the royalty checks and the weird hype and no sleep finally kills him or burns him out, we’re gonna miss that guy soooo much and be amazed we didn’t realize what we had.

EDIT, JAN 17 2020:

I was right.

----

*Even the very word "speech" here is rhetorical sleight-of-hand--directing your attention to the brandished shiny ball while rustling around with something much larger under the table. "Speech" implies a statement--a position for-, or against-, something and we (tbh) evaluate our position based on whether we agree with the 'something;. "Freedom of Art" sounds shitty and pretentious but is a more complex idea, as everyone who ever seriously deals with art will tell you even the worst always ends up "saying" more than one thing, and keeps doing that--even after the artist dies. Reducing that reducing a creative work to "speech" allowed Grove's enemies to reduce something like Tropic of Cancer to a political position: The Beatnik Left, which is a lot easier to argue against.

-

-

-