Fifth in a series about D&Dables in Art History

The best of Indian art generally falls into three broad categories, each with their own fairly distinct aura:

First, there's folk art--

These are objects in all media and a bewildering range of styles made all over India because someone, somewhere felt like it.

Here's a drawing somebody did of some guys hitting each other:

…it matches no other style on the continent or, really anywhere else.

Similarly, these look like they could've been made on any planet so long as it wasn't ours:

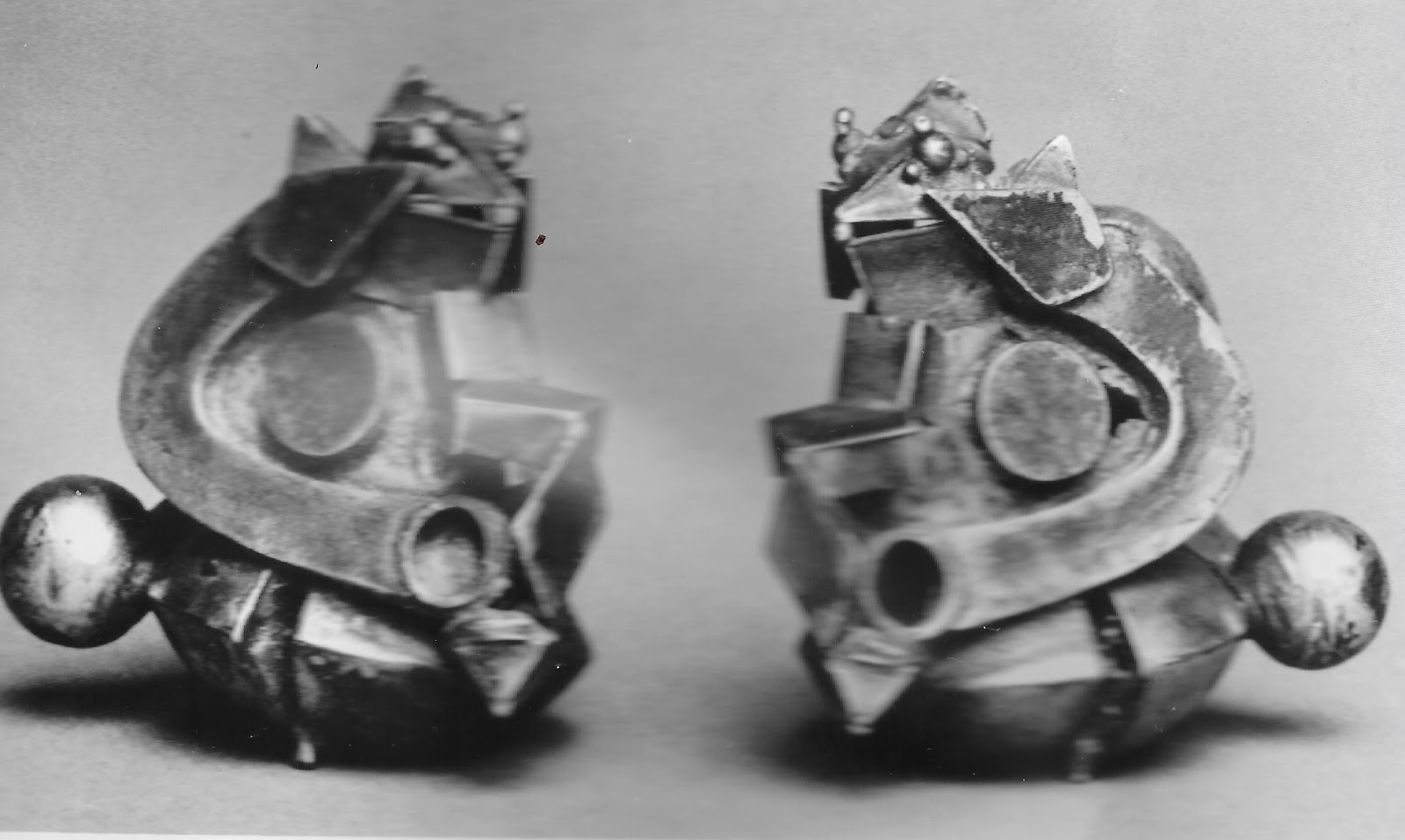

|

| Earring or Iron Golem? |

Different as the earrings and the abstract dudes fighting, they have a certain set of qualities--densely composed, vivacious, playful, curvy--which come out in a lot of the other art of the subcontinent.

The second category is richly decorated luxury objects…

This is an elephant goad and an amazing piece of sculpture. Enlarging it lets you see how the whole thing is hollow, plus all the dozens of different animal shapes worked in. While Western art basically went up to the Medieval period with the weird monster art and then took a long breather to try to figure out how to make people, India just kept going with the monsters, making ever more refined, inventive and insane zoomorphic and teratomorphic shapes and giving them new things to do.

Ustad Mansur was the star animal painter at the court of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir, he made one of my favorite paintings of all time:

|

| I love this fucking painting. It is unbelievably charming. See the butterfly? The chameleon's totally gonna eat that butterfly. |

The Mughals were an Islamic dynasty and Indian painting during this time is very similar to Persian miniature painting (about which more later). These kinds of paintings have something of the design sense of east Asian painting while still having something of the very European desire to get everything in and get everything right.

A Chinese painter would've more ruthlessly subordinated the branches, animals and leaves to an overall design so the whole picture looked like it was one elegant gesture while a Western painter of the same period probably would've tried to make the chameleon look as much like an observed chameleon really sitting on a branch as their technical skill would allow while also trying to make the composition look like it all just happened to be that way (but covertly fitting it into a cross or a triangle or some other eye-pleasing organization of shapes). This painting is a third thing: the curve of the branch and tail are obviously the way they are for the convenience of the image, but each object's texture and color has been rendered carefully and independently, with no desire to "push" any of the elements back in order to create a unified whole. Each object is its own thing, and can be examined separately or as part of a pattern.

This lion works much the same way: the head is done in a sort of bulbous style reminiscent of Chinese lions but then the mane is done totally differently in layers of fine-lined hair, then the torso is done in a highly stylized, muscular way and the tail could've been snipped off the chameleon. A single animal is conceived as a collage of differently patterned and decorated parts (which, if you read old naturalists' and fabulists' descriptions of new animals, is how they're described in words).

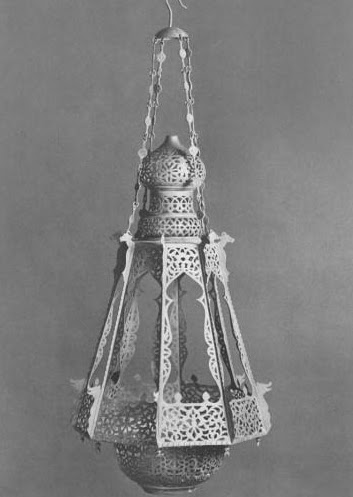

Lanterns generally echo their cultures' architecture in miniature and this very Taj Mahally one's no exception.

|

| They made a pig cannon. Awesome. |

|

| Emperor Jahangir's friend Imayat Khan was wasting away from opium addiction so the emperor was like, Better have somebody paint him c. 1618 |

Mughal miniature paintings are very video-gamey in both the way they use space and the way they use color and pattern to differentiate figures from each other. It's a really good format for illustration-as-diagram style pictures or things with hidden clues.

|

| This is a chair-leg. It's typically Indian that, even detached from the whole, it's still a sculpture in itself. |

Third, There's Temple and Religious Sculpture

I don't plan on doing too much architecture in this series because if I did we'd be here all day but I'd feel remiss if I didn't at least show a little Indian stone temple architecture because these things are mind-blowing and there is an off-chance someone doesn't know that:

|

| Lingaraja Temple. Holy fuck. C. 1100 |

---11th-Century-Pala-Period-Buddhist-Sculpture.jpg) |

Sometimes you'll see the same face ten or twenty times in a row on human-faced deities but figuring out how to do Ganesh's face and big belly often pushes artists to try something new.

|

Srirangam Temple. These date from the Vijayanagara period (1336–1565)--again there's that Gigerish, almost unfollowable, density of shapes.

The eyes on suave Ganesh here stand in contrast to the inquisitive slits on the previous Ganesh, and the pose is more naturalistic than symbolic.

|

This sandstone apsara (sexy female nature spirit, see also yakshi), known as the Dancing Celestial was made in the 12th century in Uttar Pradesh and is at the Met...

…her pose is known as the tribhanga (or 'three bends') and is pretty common in Indian sculpture and dance. It's kind of the less douchey, more fun-loving version of Greek art's contrapposto pose. Tribhanga's like Oh My God I Love This Song and Contrapposto's all Oh, That's Cool, I Used To Like This When I Was In High School I'll Be Over Here In The Corner Hoping Everyone Notices My Hair.

Now click this and enlarge it:

This is Durga killing Mahisha--a buffalo demon--from the Pala Period. There are a million cool things about it, but three of the less obvious ones are:

-it's tiny--shorter than your hand with fingers extended

-Durga has, among other weapons, a chakram, which is like a murder-Aerobie

-the way Durga has decapitated the bull (very cleanly) and the head is just sitting there and she is just literally yanking the demon right out of its neck.

Whoever made that would've had a very promising career at Forge World had they been born in our century.

This is Chamunda, 8th century. Speaks for itself, really.And this is an Indian stepwell, which has nothing to do with anything but is worth noting as probably the most D&D-looking place ever:

13 comments:

Yes, the architecture...

Had the opportunity to visit the Ajanta and Ellora cave temples several years ago. Complexes carved into the basalt of the evocatively-named Deccan Traps... Dense with carvings and bas relief. Great environment for an adventure setting.

And of course, the 'erotic' temples of Khajuraho. Again that dense giger-like carving in sandstone. Figures from hand size to greater than life size. The most striking figure (other than the prince having sex with three women while suspended on a platter held by servants) was a courtesan stepping from a bath, naked but for a linen wrap clinging to her hips. Again, all depicted in carved sandstone.

Etruscan art would make a nice feature - made great contrast with roman realism when they added romulus and remus to that wolf - shang chinease and mesomerican art and eutruscan sculpture go together niceley - when romans becoming christian they increasingly got more simple and abstract in sculpture yet painting on coffins got realistic and logic and philosophy and science were increasingly replaced by miracles - galen who preached scientific method was taken is immutable dogma for over a thousand years completely contrary to his teachings - cultural takes and changes on realism very interesting

Thank you for this! India is a big influence in my 5e campaign, and there was some stuff here I'd not seen before. Clawed elephant beasties absolutely need to make an appearance, I'm thinking.

And trip to the Met scheduled for Christmas!

Very cool post again, Zak ! But I have something cooler to share ! The islandic goat, one of the most metal beast on Earth, is free and saved ! The indiegogo CF campaign https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/save-the-icelandic-goat-from-extinction/x/5065177 is successful ! You can be proud of your part in its preservation !

this series is really great, i want you to continue it forever.

who knew that a professional artist would know interesting things about art history?

Enjoying this series enourmously. In my opinion this was the best post sofar, but only because I hardly know anything of this geographical region and learned a lot.

God. Damn.

That fractal density is so great.

Anyone interested in the D&D-izing of this subcontintent should check out Arrows of Indra.

http://www.bedrockgames.net/about.html

This is a warning: Do not leave comments that are just ads.

The "D&Dables in Art History" series is a true opener of eyes and mind! Thank you very much Zak!

Giger certainly had thses types of asian and gothic themed art as reference. I can't find the source now though. But I definitely know of that.

Great post by the way. Om!

Post a Comment