First--here's another Maze of the Blue Medusa preview:

|

| Click to enlarge and...SPOILERS! |

If you're new to the contest, it's like this: these two essays are not by me--they're by a pair of anonymous DIY RPG writers who were both assigned to write something interesting and original about hoary old RPG topics.

Anybody reading is eligible to vote for which one you like best and voting will be cut off once all the votes for all the second round Thought Eater essays are up...

The rules for the second round are here.

First One

If you like this one better, send an email with the Subject "MAJ" to zakzsmith AT hawt mayle. Don't put anything else in the email, I won't read it.

First One

If you like this one better, send an email with the Subject "MAJ" to zakzsmith AT hawt mayle. Don't put anything else in the email, I won't read it.

OK, so horror in H.P. Lovecraft's fiction comes from the revelation that things are not like you thought they were. Often – in the most famous stories – this is specifically the idea that humankind is merely a tiny speck in an infinite, uncaring – heck, possibly malicious – cosmos. Everyone's heard that; it's kind of the stock explanation of how Lovecraftian cosmic horror works. In many other stories, it comes from the idea that the main character is not who he thought he was. Specifically, in Lovecraft's fiction, it often comes from the idea that the main character's ancestry or history is not what he thought it was. Charles Dexter Ward, Shadow Over Innsmouth, The Rats in the Walls, Arthur Jermyn … you know the kind of thing. “The Shadow Out of Time” combines both themes in a way.

Now, this idea of being annihilated by having your history or group identity undermined is one that clearly resonated very strongly with Lovecraft himself. If you read about him, you can see why: “Take a man from the fields and groves which bred him—or which moulded the lives of his forefathers—and you cut off his sources of power altogether.” He wrote that in 1927, and in 1934 he said “We must save all that we can, lest we find ourselves adrift in an alien world with no memories or guideposts or points of reference to give us the priceless illusions of direction, interest, & significance amidst the cosmic chaos. Hence the natural function & social value of the antiquarian & cherisher of elder things.”

So rather than being impersonal, Lovecraft's cosmic horror is actually very personal, because to him your history is a big part of you – even if that's the history of your city, your race, whatever. That combination of the personal and the cosmic is an often-overlooked part of Lovecraft.

How do you use this kind of history-undermining or group-undermining in a game? The unfortunate thing about applying this to Call of Cthulhu is that most people don't create their CoC characters with those kind of deep ties to a group – like most modern people, and like characters in many other games, they tend to be pretty atomised, pretty individual. You can't really attack their sense of stability by revealing the secret history of humanity, since thinking that's pretty cool is implicit in sitting down to the table to play CoC in the first place. It's hard to attack the group, as opposed to individual, identity of player characters in these games – in the same way that it's hard to do that to most (but not all) modern westerners.

But I've been thinking that this does in fact apply to characters in a lot of other games. In fact, ironically, it applies to them much more than it does to characters in games that are specifically Lovecraftian. In many games, character creation is all about selecting group memberships, and there are lot of people out there who make it a habit to play Ventrue, or Orlanthi, or mutants, or Drow, or whatever. You might actually be able to get some mileage out of the history-annihilating thing by attacking those, especially if you keep the secret actually secret and don't make it part of the appeal of the character. Some people like to join groups with a dark heritage, but if someone's really proud of their sparkly eyes or elite battle skills you can probably get a little queasy realisation by revealing that their blessing is actually a curse.

That's not for everyone, of course; some people like the rug pulled out from under them and others don't. You might just piss them off. But that's the risk you take when you go for an actual shocking realisation.

-

-

-

Second One

If you like this one better, send an email with the Subject "UAP" to zakzsmith AT hawt mayle. Don't put anything else in the email, I won't read it.

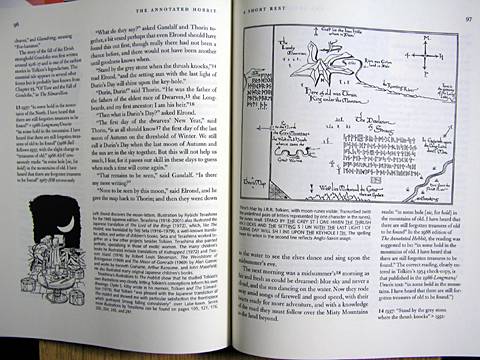

The Annotated Adventure

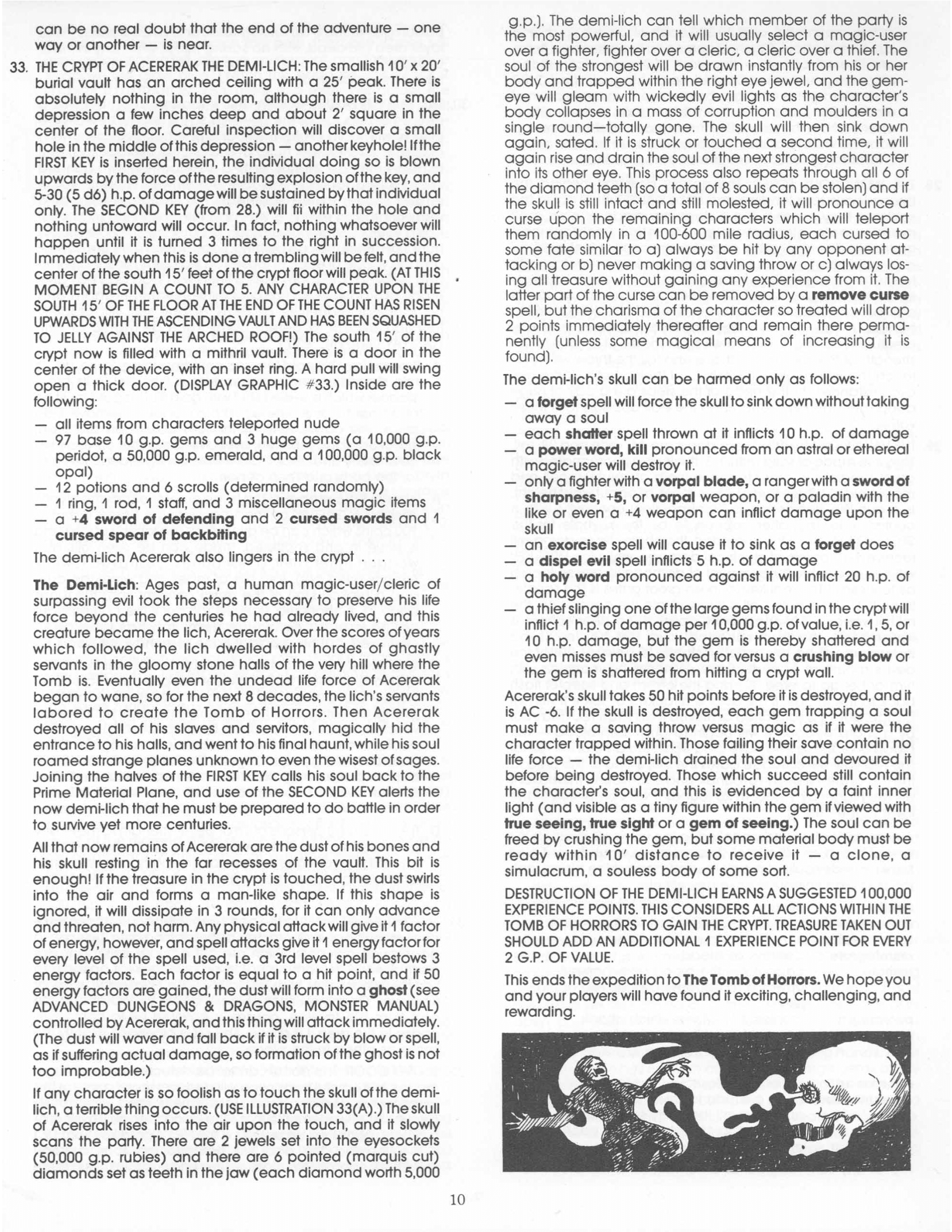

Published D&D modules are typically laid out like dictionaries: dense columns of prescriptive rules, sorted by location instead of by word. They'd be more useful if they were designed more like annotated texts (text body in one column, commentary in the other). When there's no spatial way to organize room descriptions, they become untidy with digressions, commentary, and rulings on potential player actions. The important and the unimportant, the obvious and the hidden are necessarily jumbled together.

Tomb of Horrors is famous for being a player-killer dungeon, but with its info-dump approach to tricks and puzzles, it's a bit of a DM-killer too. Take the final confrontation with Acererak. It takes up a full two-column page, and you don't get Acererak's stats until the bottom of the second column, after a description of his treasure, an out-of-place history of the Tomb, and the details of every other trick in the room. Furthermore, this monolithic wall of text gives the false impression that everything in the description merits the same level of authority. As others have remarked before, many of the methods used to damage Acererak (a haphazard list of spells, certain magic swords, a thief slinging gemstones) feel like on-the-spot rulings during a playtest, encoded by the author into rules law. There's no reason why clever players shouldn't invent new attacks and add their own exploits to this list, which should be presented as a sort of Talmudic commentary to the module's scripture that "Acererak is nearly invulnerable."

What would an annotated adventure module look like?

The main column would be primarily concerned with objects: the room and its description, its contents, its occupants, immediate traps, and other information that the DM needs up front. Objects in boldface would have annotations next to them.

Next to each boldfaced object would be its verbs: a non-exhaustive menu of things the players might do and what happens in response. Here is where we'd move all the minor but necessary mechanical details that clog up room descriptions: the tricks, traps, and secrets that players find by messing with stuff in the room. If a player touches Acererak's skull, the DM doesn't have to search the whole page; just find the bold-faced "Acererak" in the main column and scan its annotation.

Annotations can't possibly be comprehensive and don't even have to be authoritative. They might include traps and puzzle solutions, described in the standard impersonal rulesy voice, as well as conversational anecdotes about crazy things that happened in the author's home game. After all, half of every adventure is written during play; the module author doesn't need to obfuscate that fact.

As a proof of concept, I'll try setting up the Acererak room as one annotated page. While I'm reformatting, I'd like to fix a few other things that bug me about D&D module layout:

Space for DM annotations. A D&D module isn't a collector's item to be preserved mint, and an adventure location isn't static. PCs change every room they enter. The DM should have somewhere to record these state changes. For instance, there should always be space below a monster's stat block to track HP. If the players befriend the monster instead of fighting it, the DM can use this space to record details of that alliance. (Chances of befriending Acererak are low, but never rule anything out.) Furthermore, many DMs don't run modules as written. They make lots of notes before ever running the adventure. A densely printed page doesn't leave a lot of room for this kind of marginalia. An annotated module, with uneven amounts of text in the right and left column, will probably have lots of white space. That's a plus.

In the case of Acererak's vault, we're going to have very little room for DM notes, because the original layout is already a full page with no white space or margins to speak of. But we should be able to carve out some room to track Acererak's and his pet ghost's HP. Furthermore, the vault's treasure includes a potentially large amount of gear stolen from players in various teleportation traps. We have to add a place for the DM to list this gear.

Artwork. Tomb of Horrors has many pages of player handouts, two of which are referred to on this page. The reference to any player handout should include a thumbnail for the benefit of the DM.

Here's my version of Acererak's Vault, with significant text changes in red.

-

-

-

No comments:

Post a Comment