If you're new here, it's like this: these are not by me--they're by a pair of anonymous DIY RPG writers who were both assigned to write about: Group Dynamics for the contest.

First One

If you like this one better, send an email with the Subject "DYNAMIC1" to zakzsmith AT hawt mayle or vote on Google +. Don't put anything else in the email, I won't read it.

When the whole is less than the sum of the parts

Recently, I terminated my Vampire campaign after only a handful of sessions. The reason? The players developed a certain hostility towards each other undermining our weekly evening of gaming fun.

This is a personal example of group dynamics going awry. Often, when complaining about a player's behaviour, it is recommended to replace that player, or find a new gaming group altogether. Although this might indeed solve the problem, it is often preferable to look for an answer within the current group.

Within the field of gestalt psychology Kurt Lewin proposed the equation B = f(P,E) to describe one's behaviour (B) as a function (f) of both her personality (P) and the environment (E). Later, he applied his equation to groups by observing that the environment for one individual includes the behaviours of the other group members. This results in a set of coupled equations, with each equation describing the behaviour of one member, requiring the behaviours of all others as input. The solution of this set forms the basis of the research field known as group dynamics. The equations are heuristic in nature, in the sense that they do not solve the dynamics mathematically, but help to align our thoughts on the matter.

In order to deal with negative group dynamics within a game of D&D, all we have to do is determine the cause(s) of undesired behaviour in terms of 1) personalities and 2) elements constituting the environment, and then take action accordingly.

Bad group dynamics is often explained by bad personalities. This explains why the most-offered advice is to expel a player. From the equation above, however, it follows that the dynamics are rather dictated by undesired behaviour. And although, this might in turn be induced by certain personalities, it is an oversimplification to state that bad personalities will always result in undesired behaviour, since the latter is also a function of environment. It might even be that, with the right set of environmental parameters, a 'bad' personality will lead to desired behaviour.

In case of D&D, the environmental parameters fall into three categories: 1) Behaviour of the other group members, 2) elements of the game, and 3) non-gaming elements.

Since behaviour induces behaviour, the first category is an important one. Hostile acts may prompt retaliation actions. Or, disproportionate amounts of spotlight time given to one player may cause non-involvement in the other players. This, in turn, can be the feeding ground of boredom and the loss of focus leading to non-game activities like chatting or playing with mobile phones. Also positive acts can induce undesired behaviour. An in-game joke may lead to another, non-gaming-related, story, for instance.

Also the game itself may be debit to bad group dynamics. By the nature of the game, it facilitates certain behaviour based on the assumed roles. A common excuse to misbehave is: 'I do this, because it is what my character would do'. Think of thieves stealing from party members and the 'lone wolf' who is deliberately not involved. A more subtle aspect of the game may be that one character is more suited to do a certain thing than the others, giving her player an excessive amount of spotlight time: 'My character should do all the talking/sneaking/scouting'.

Finally, there is the broad category of 'anything else'. This encompasses anything from a foul mood because my cat died yesterday, to the game location with all these interesting miniature on display causing distraction. Part of these fall in the once-in-a-while category and probably do not have to be dealt with; just endure the one time things do not work out perfectly, and pick things up next week.

The final step is, of course, addressing the cause and talking about it. Specifically asking input from quiet players, change of character, 1 hour chatting before game play, telephones from the table, different game location, the solutions are many. One specific type of solution needs special mention and that is the in-game solution. Sometimes, an improvement can be achieved by changing the game or campaign. For instance, the lone wolf must become a full party member as part of an assignment making her more cooperative. Make the thief who steals from her party members realise that this has alignment consequences. Device a setup such that the party spokesman is not the most-suited to speak up. Be creative!

In short, when group dynamics go askew, it is worthwhile to look beyond player's personalities. Even when not the cause, a change in game or non-game environmental elements might be enough to overcome the group problems.

In case of my terminated Vampire campaign, it was my own fault that things went down-hill. Only one player had played Vampire before giving me the opportunity to hand out information on a need-to-know basis. This made information valuable. In addition, politics was an important aspect of the campaign. When the players joined different factions, they became de facto competitors; information was not shared anymore, and fights broke out. In principle, I could have repaired the campaign by changing some aspects within the game. For instance, I could have sent them on a quest far away from the political arena. But, that is not what I decided to do ...

... I terminated the campaign in favor of AD&D. Because, AD&D is more fun than Vampire anyway.

Second One

If you like this one better, send an email with the Subject "DYNAMIC2" to zakzsmith AT hawt mayle or vote on Google +. Don't put anything else in the email, I won't read it.

Group dynamics, the interactions of a group of people engaged in a social group (or game), are of extreme importance in RPGs. These are social games. Played amongst friends or strangers, the nature of these games is cooperative storytelling with the added twist of chance for the success of the narratives. The internal operations and behaviors of the players at the table are crucial to the enjoyment of the game. Most players and game masters are aware of this on some level and much has been written about it. The behaviors of the players influence the behaviors of their characters in game to varying degrees. Different groups play with different desires and as some are just looking to play themselves with magic or a big sword, others really enjoy getting into a character. As such, their characters may present the group with a different dynamic in game than their players do around the table. An experienced group can handle all of this with relative ease and the changes in dynamics between players and their characters can make for enjoyable story telling opportunities.

But what about the monsters?

What about the NPCs?

The villains?

As these actors are imagined, voiced, and controlled by one player, the game master, it is difficult to observe in them the same group dynamics we expect to see in the players. Often the dynamics are assumed. The biggest monster, or highest level NPC, is the “leader” of whatever group (if there is one) they are associated with. But is this realistic? Does it smack of verisimilitude or is it simply an easy approach to tailoring and encounter? Think about real groups in the real world. A brand new Lieutenant in the Army is not nearly as experienced or dangerous as his platoon sergeant, a veteran of years of training or real warfare. Yet the Lieutenant is in the position of authority. Why would this not occur as well in the monster or NPC encounters we craft at the table?

The dynamics that arise from unexpected leaders and followers can make for more interesting encounters. Imagine the following encounter:

"Astride a nightmare sits a robed and hooded figure, slouched in the saddle and carrying a staff. Between the nightmare rider and the party, four skeletons, bones yellowed with age, but glowing eerily in the dusk, advance towards the group."

This description paints a familiar scene of a group of low level undead approaching the party, apparently under the control of the rider. Many parties, experienced in the game or at least with stock horror concepts, would plan to target the rider as a priority. They would infer from the description that the rider is somehow in control of the undead, or at least more dangerous. However, if we create the encounter with the skeletons as the leaders (perhaps they are the long dead remains of a group of low level necromancers that managed to combine their negative energies to summon a nightmare and rider…) we throw a surprise at the players. As they focus their attack on the nightmare and rider, only to find it is an illusion, or worse, invincible to their damage, they find the skeletons more dangerous than they expected. In the course of the battle, as they destroy the skeletons, the nightmare and rider become vulnerable to damage, or slowly weaken in relation to the destruction of the skeletons. Any number of ways to play this out exist. The point is, by altering the dynamic of the group encountered, a game master can make for more memorable play than just another minion to master grind.

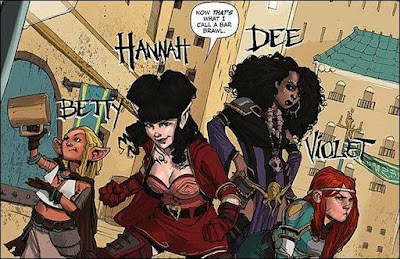

With sentient creatures or humanoid NPC parties, the dynamics can provide even more interesting options. That rival adventuring party that has been exploring, fighting, and facing the challenges of the world together, just like the players’ party, has developed internal dynamics. Who loves who? Who hates who? If the leader dies in combat, who will still fight and who will run? Who will assume control? If someone attacks the wizard, will the rogue stop what she’s doing to defend him because of their relationship? Does that rival party even get along, or are they all looking for a chance to let one of the others perish…? By developing this information, the encounter can be given further depth and if the encountered party is to be a recurring rival for the players, their internal dynamics may become more important as time goes on. (Sentient creature groups can be examined and developed in the same way. Maybe the goblin is the leader of that group of hobgoblins because of a religious prophecy that the hobgoblins will all die to protect…)

The point of all this is to invigorate your encounters through the application of some basic group dynamics. These encounters will prove more memorable and challenging for your players without necessarily increasing the actual stats based challenge of the scenario.

Now since this is about gaming, an essay is only as good as its use in game. Here’s a quick mechanic I worked up to develop the dynamic for a randomly encountered group (or a group in a published adventure that lacks any info on the dynamics of its members…)

- Quickly assign a number to each creature/NPC/monster/whatever in the encountered group.

- Roll an appropriate die to determine the leader, i.e. for 8 creatures, roll a d8. The number rolled identifies the leader.

- After identifying the leader roll a d10 and consult the table below. Play as described.

1-All (or some) members of the group are loyal and will sacrifice themselves to protect the leader

2-All (or some) members of the group are disloyal and will not help the leader (may even try to sneak a hit in)

3-One member of the group is in love with the leader (roll to determine). That member will behave accordingly.

4-One member is the object of the leader’s love (roll to determine). The leader will make decisions based upon that interest, potentially at the cost of the group.

5-The leader is loyal to the whole group and will tell them to flee a losing encounter, remaining behind to protect them or slowing the pursuit.

6-The leader does not care about the group and will send them to their deaths without hesitation, but will save self.

7-Two members love each other (roll to determine who loves who) and will behave accordingly.

8-Two members hate each other (roll to determine who hates who) and will behave accordingly.

9-No one trusts the competence of the leader. Will ignore most orders (determine by rolling under/against wisdom or intelligence stat)

10-The leader is only a puppet of one of the other members (roll to determine) and if killed will be replaced as leader immediately by the other member.

-

-

-

No comments:

Post a Comment